|

|

|

View from the west |

View from the southeast |

José Maria Alviso Adobe/Rancho Milpitas

|

|

|

View from the west |

View from the southeast |

The right to the lands that came to be called Rancho Milpitas (meaning roughly, "little gardens") was contested by two men. The oldest claim was that of Nicolás Berryessa, who had received it as a grant from the alcalde of San José, Pedro Chaboya, on May 6, 1834. The second claim was that of Berryessa's former comrade in arms, José Maria de Jesus Alviso. The two had served together as soldiers at the Presidio of San Francisco for eight years. Alviso had applied to the governor of Alta California, José Castro, for his title to "the land known as Milpitas" which he received on September 23, 1835. A second grant or addendum to the first grant was signed by Castro on October 2, 1835. It enlarged the first grant by one league to the west, making the western boundary Penitencia Creek. Alviso named it Rancho San Miguel and that is the name that appears on the first deed to land sold from the ranch made on February 14, 1856 to Michael Hughes. It is likely Alviso built a residence on the land in 1835 when he received his land grant. [See: Origin of Milpitas video]

|

|

Alviso and Berryessa were both prominent

citizens of the South Bay decended from Spanish pioneer

families who arrived with the Anza expedition. Alviso's

father had been Francisco Xavier Alviso, who was born in

Sonora, Mexico, and who, at age four, was one of the three

children who accompanied the Anza expedition. Berryessa

was rigidor of San José in 1836 at the same

time Alviso was serving as alcalde. In 1841, both were

living with their families in San José, although by

that time Alviso had already built the first story of the

adobe house still standing today near the banks of Arroyo

de los Coches (Los Coches Creek). At left is view from the south. |

| The original large adobe house was joined by three others to the south along the old Piedmont Road. Eventually, Alviso had brought his family to live on the rancho. The rancho was part of the outlying area of the Puéblo of San José. The town folk maintained gardens of squash, corn, beans and other crops along Pennitencia Creek and Coyote Creek. Alviso, too, grew crops on his land but mostly ran cattle. The primary source of revenue to the local landowners during the Spanish and Mexican years was cattle hides. When Frémont's first expedition stopped overnight at Rancho Milpitas they noted the horrible stench from rotting cattle carcasses butchered for their hides. |

|

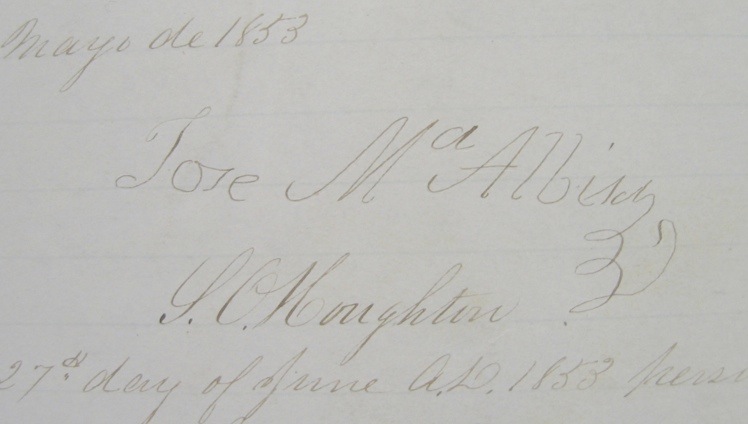

[Signature of Jose Maria Alviso

dated May 1853 from a deed of land transfer with S.O.

Houghton. Alviso died before the transfer was completed so

Houghton had the deed redrawn and all of Alviso's heirs either

signed or made their marks to it. The first deed was written

in Spanish and in English but the second version was only written in

English. Houghton was a prominent lawyer who married two

cousins, survivors of the Donner party.]

[Signature of Jose Maria Alviso

dated May 1853 from a deed of land transfer with S.O.

Houghton. Alviso died before the transfer was completed so

Houghton had the deed redrawn and all of Alviso's heirs either

signed or made their marks to it. The first deed was written

in Spanish and in English but the second version was only written in

English. Houghton was a prominent lawyer who married two

cousins, survivors of the Donner party.]Near the time when Alviso died in the Summer of 1853 the second

story we still see was built. The house looks today much as it did

when, according to Bart Sepulveda, an Alviso descendent, Alviso's

youngest daughter, Maria de los Angeles Alviso eloped with the

well-known bandito, Bartolo Sepulveda by slipping down to his

horse from the second floor balcony (a story disputed by other

family descendents, but nonetheless a very romantic one).

|

Later, in 1858, Juana Galindo Alviso, widow of José Maria, married Josè Urridias, who as manager of the rancho, gradually sold off acreage as needed for cash. Maria de Los Angeles Alviso Sepulveda inherited the adobe and the land immediately surrounding it. The family sold much of it and eventually it was acquired by the Cuciz family from the Gleson family about 1922. The Cuciz's planted orchards of fruit trees, built a water tankhouse, a barn (partly constructed of timbers salvaged from the three adobes south of the main house), a carriage shed, drying shed, power generator, and other improvements. The Cuciz family sold the property to the Calvary Assembly of God Church in the early 1980s. The adobe remained inhabited from the time it was built until it became city property - perhaps the oldest continuously inhabited adobe home in California. |

| View of Cuciz' fruit drying shed located east of the main house. | The City of Milpitas acquired the adobe in

1996. The house is now on the National Register of

Historic Places. In 2009, the adobe was stripped of

its historic mud and plaster coverings. Repairs to

the adobe bricks were made, a new covering was put on and

painted with lime whitewash similar to the original.

A modern roof replaced the original, earthquake bracing

and shear walls were added to the interior along with a

new wood floor. The city has plans to complete restoration

of the adobe at some time in the future. The

outbuildings constructed by the Cuciz familly in 1922 were

destroyed by the city in 2012 as being

"unsalvageable" and new versions of them were

reconstructed. The ancient apricot and walnut trees

dating from the Cuciz original orchards were removed to

make room for a picnic area and restroom, but new fruit

trees have been planted in the park. Over a 20 year

period, the Milpitas Historical Society contributed

$100,000 to the preservation and reconstruction of this

site. It is hoped that the new Alviso Adobe History

Park will remind visitors of what an early twentieth

century fruit ranch might have looked like. |

![]()